TODAY marks the 75th anniversary of the end of the Second World War, with the Japanese surrender bringing to an end six years of conflict. Nicholas Thomas spoke to Newport historian Andrew Hemmings about two of the city’s wartime heroes.

On August 15, 1945, Japanese Emperor Hirohito announced to his people that the nation would surrender to the Allies, marking the end of the Second World War.

For people living in – and fighting for – Britain, the Japanese surrender brought an end to nearly six years of the death and destruction in the global fight against the Axis powers.

The surrender of Nazi Germany, prompted by Hitler’s suicide and the arrival of the Soviet Union’s Red Army in Berlin, had signalled victory in Europe on May 8; but the bitter fighting in the Pacific theatre continued on for another three months, with the Japanese resisting fiercely the Allies’ hard-fought advances.

The atomic bombs, dropped by the Americans on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9, respectively; coupled with the Red Army’s advances across Manchuria, had convinced the Japanese military leadership to surrender, and on this day 75 years ago, the war was brought to a sudden end.

The Second World War was a truly global conflict, and the people of South East Wales – both military and civilian – played their part in Britain’s victory.

Local historian Andrew Hemmings, the author of Secret Newport, has on the 75th anniversary of the war’s end penned the stories of two Newport seafarers to remember the heroism and sacrifices of people from the city.

Wilbert Charles Roy Widdicombe was born in Totnes, Devon in 1919 and became a merchant seaman, marrying Cynthia Pitman at Holy Trinity Church, Newport in March 1940.

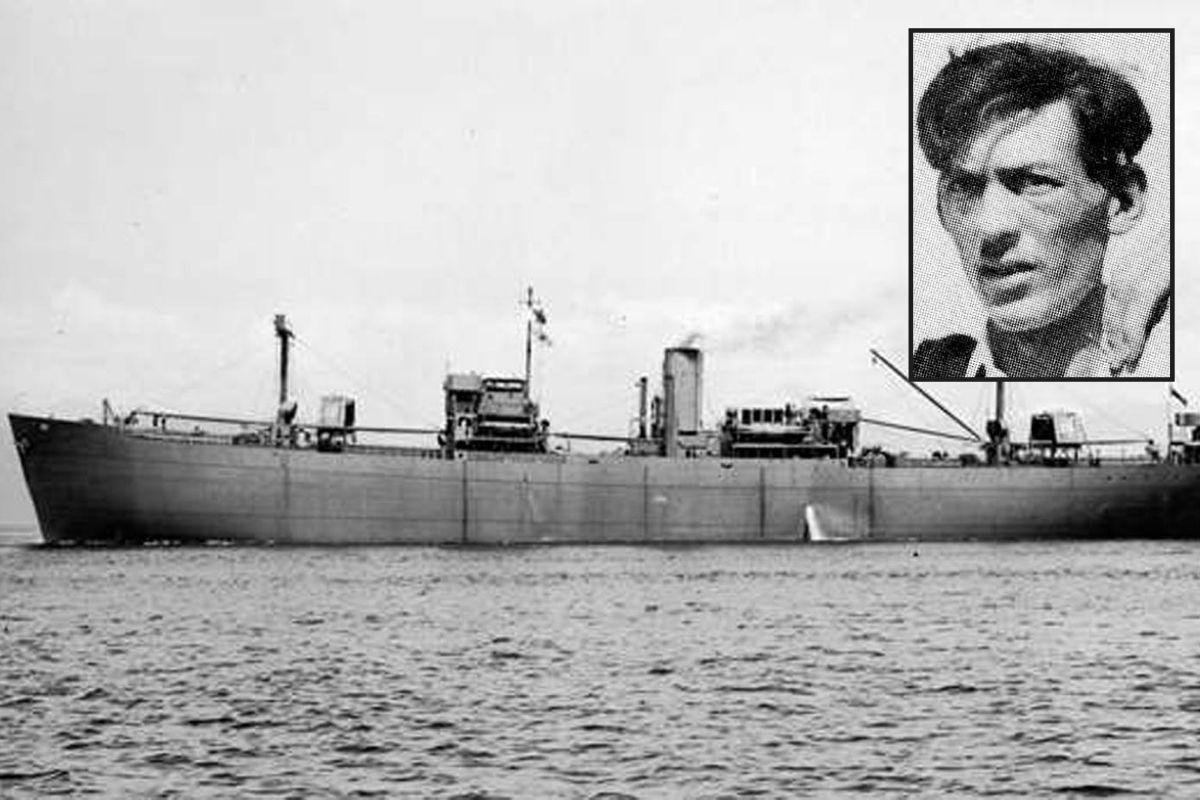

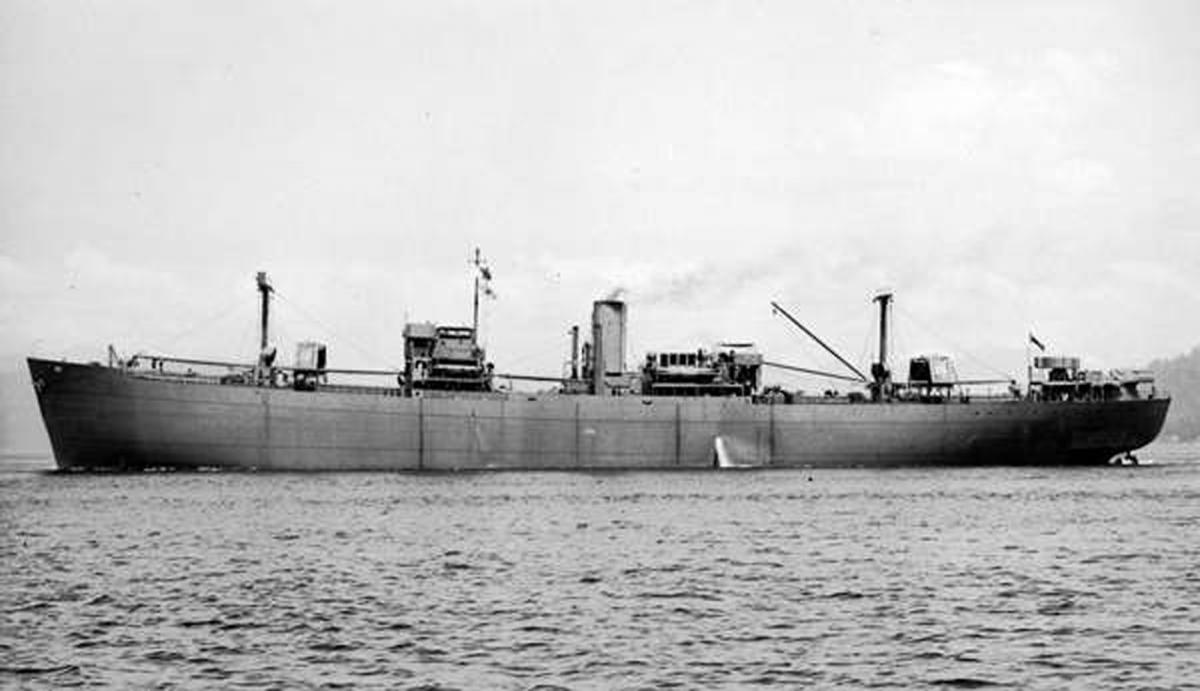

On August 21 that year, his ship, the SS Anglo Saxon, was en route from Newport to Bahia Blanca in Argentina with a cargo of coal when it was attacked by the German surface raider Widder, disguised as a neutral ship, in the Atlantic Ocean off West Africa.

Able Seaman Widdicombe was in the wheelhouse when the vessel was strafed with machine gunfire and torpedoed. He managed to lower the ship’s one undamaged ‘jolly boat’ into the water despite injuring his hand. The seven surviving men, from a crew of 41, had few provisions in their lifeboat – a little water and food, a compass and oars.

Over the next fortnight, five of the men died, some as a result of injuries from the attack on the ship. Others threw themselves into the sea, deluded from hunger and thirst. After 19 days, only two remained aboard – Roy Widdicombe and Robert Tapscott.

MORE ON NEWPORT'S MARITIME HISTORY:

- Remembering Newport sailor who braved U-boats and Arctic waters on 'the worst journey in the world'

- 'Lunacy and bravado' - Newport stowaway on Shackleton's Antarctic voyage stars in new book

- How First World War hospital ship Glenart Castle was sunk by a U-boat after leaving Newport, killing 162

Incredibly, 70 days after the SS Anglo Saxon had been sunk, the ‘jolly boat’ grounded on a beach on Eleuthera Island, in the Bahamas. Barely alive, the pair had lost half their body weight and were severely sunburned. They had survived by eating seaweed and collecting fresh water on the few days it had rained.

For the last eight days of their journey they had no water and had smashed their compass to drink the fluid from it. They were taken by seaplane to a hospital in Nassau, the Bahamian capital, where they recuperated over many weeks.

The survivors later toured the United States to promote the plight of Great Britain before the US entered the war. But Able Seaman Widdicombe’s moment of fame was short-lived – Britain needed every sailor it could muster for the merchant fleet – so he travelled back home.

He was only a day away from Liverpool when a German U-boat torpedoed the SS Siamese Prince off the coast of Scotland, with the loss of all hands.

There were no medals nor blue plaques for Roy Widdicombe, but he is remembered by the display at the Imperial War Museum London of the ‘jolly boat ‘ from the SS Anglo Saxon.

Edward Alfred Dyer of Newport was awarded the British Empire Medal (Civil Division) following his exploits as boatswain on board SS Fort Chilcotin. This vessel was torpedoed and sunk on July 24, 1943, having detached from convoy JT2 in the South Atlantic, some 370 miles from Bahia.

The London Gazette supplement of April 18, 1944, contains the citation: “The ship...was torpedoed. The engines were stopped by the explosion. The crew had left the ship in boats and on rafts when a second torpedo hit the vessel causing her to sink almost immediately. The survivors were collected into two of the boats, which were kept together until they were both picked up five days later after making a voyage of 300 miles.

“Boatswain Dyer displayed courage and exemplary behaviour throughout. After the ship had gone down, the submarine surfaced among the boats. The boatswain was taken aboard the submarine for questioning. He was returned to his boat and thereafter, during the boat voyage, he did extremely good work, setting an excellent example to all.”

In a more detailed account of the incident, Boatswain Dyer emerges with greater credit. This is even more remarkable given that his father, Edwin Dyer, had been killed in a U-boat attack in the First World War.

Although Edward Dyer was only 17 months old at the time of his father’s death, he must have been aware of his father’s fate and the likelihood of history repeating itself in the vastness of the Atlantic Ocean.

What emerged was that U172 had surfaced shortly the attack, with its crew asking for a man to come aboard for questioning. Boatswain Dyer volunteered and told the German captain the master and chief officer had gone down with the ship. He was asked where the ship was bound but gave only vague answers, and was allowed to return to the lifeboat before the U-boat left. He later described the commander as very civil, who expressed his regret at having to sink his ship, and also wanted to hear his opinion regarding the outcome of the war.

The survivors recovered the stores from the rafts and righted the two smaller boats. They had plenty of food and water and sent distress signals from the emergency set each morning but received no replies. On July 29, they were picked up by the Argentinian steam tanker Tacito and taken to Rio de Janeiro.

“We assume that the U-boat captain conducted the ‘interview’ in English,” Mr Hemmings said. “Carl Emmerman was a very successful submarine commander who survived the war and died in 1990. For completeness, Boatswain Edward (Ted) Dyer also survived the war, living until 1985 and leaving a scale model of a sailing ship to the Mission to Seafarers, Newport.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel