SECRETS of Monmouthshire’s Reformatory School are revealed in this story of a bold strategy to divert boys from a life of crime.

In 1910 at Monmouthshire’s first Reformatory School, established in 1859 at Little Mill, one of the juvenile offenders found himself at the centre of attention for all the wrong reasons.

Teenager Robert Wood was among boys located from the Midlands following an expansion of the school’s catchment area. When the School was opened in February 1859 to cope with an increase in juvenile crime in Victorian Britain it was seen to be ideally placed between the prison at Usk, Pontypool and other valley towns.

It was destined to cater for 25 boys under 16 convicted of theft, assault or what we call today anti-social behaviour and sentenced to terms of up to three years detention.

Its impressive reputation for strict discipline and rehabilitation was noted beyond the county boundary and by 1900 numbers reached 55 including boys from Birmingham and London.

With commendable spirit Robert abandoned his criminal past and became a first rate example of a reformed character by earning merit points for good behaviour.

He was considered so trustworthy that in April 1910 he was entrusted with money to pay local suppliers for goods delivered.

Once outside and suddenly confronted with an intoxicating mix of the fresh air of freedom and a pocketful of money he was faced with a dilemma.

Should he confirm the trust placed on him or was he to be a crafty streetwise opportunist?

Adopting the Oscar Wilde’s observation that he could resist everything except temptation he strode briskly towards the direction of the shops.

Showing newfound enterprise he bought a suit and a pair of boots, hurried to the railway station and booked a ticket to Birmingham. But he was brought swiftly back to reality.

When he failed to return the school alerted the police and he was arrested.

Within days he appeared before Pontypool magistrates charged with theft, false pretences and absconding. It was felt that a more severe custodial sentence was justified and Robert now faced detention within the more restrictive regime in Borstal on the absconding charge but surprisingly no penalty was imposed on the other charges.

But this was not to be final outcome of Robert’s bid for freedom.

When the Chief Inspector of Reformatories received news of the sentence he wrote immediately to the court pointing out that the boy could not be legally sentenced to Borstal on an absconding charge as under The Children and Young Persons Act of 1908 they had no jurisdiction to do so. Therefore the school must be prepared to take him back.

The Minute Book does not record what punishment was handed out but since the birch had been outlawed by this time it seems likely that black marks, loss of privileges and fines deducted from meagre earnings of a few pence per week were imposed.

Absconding was not uncommon and at south Wales’ other Reformatory near Neath four of the 25 boys deserted. Some farmers were prosecuted for harbouring the boys.

In its early days punishments in the Reformatory regime would include being made to wash all over in cold water and then be thrashed. Such treatment, cruel by today’s standards, was deemed necessary and preferable to placing children in adult prisons. The rising crime rate in Victorian Britain led to 90 new jails being built between 1842 and 1877.

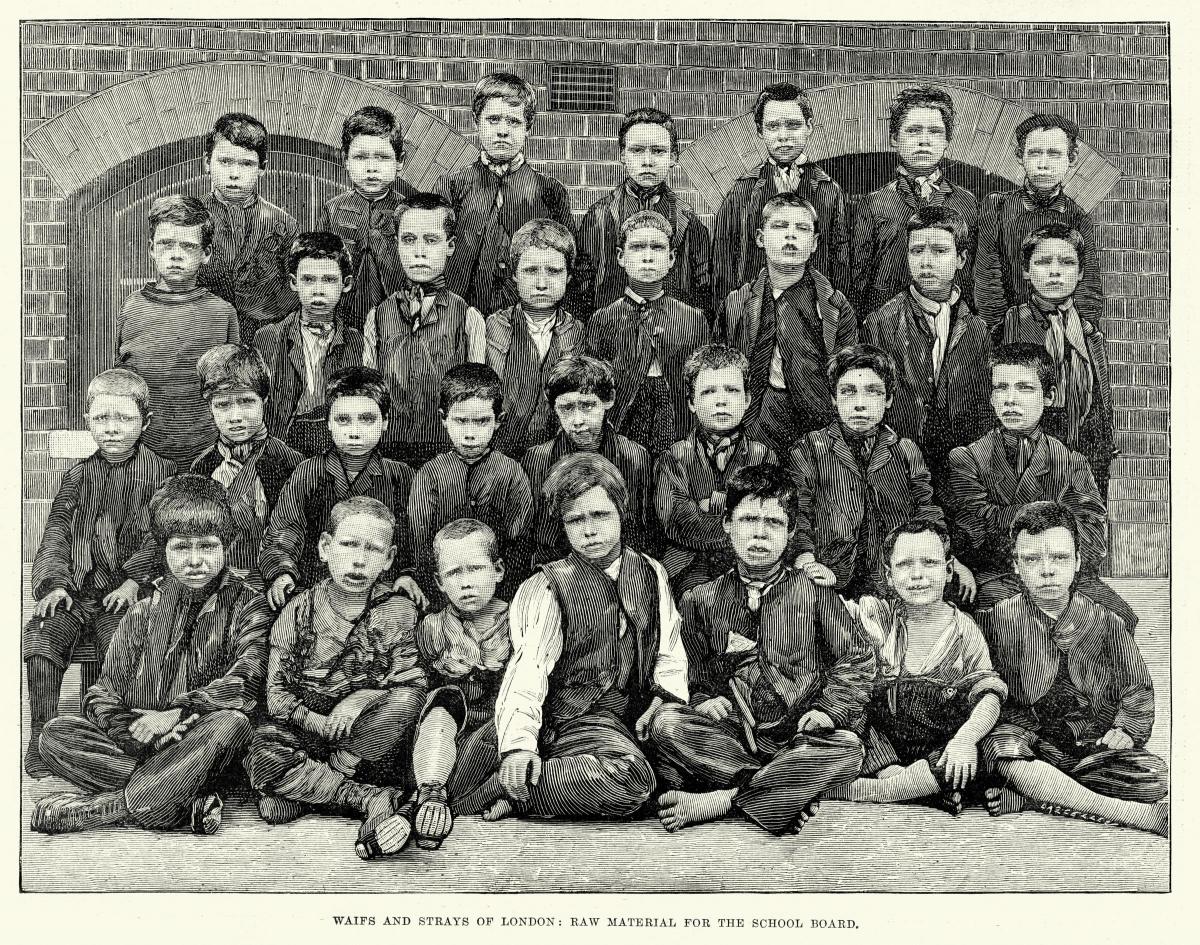

The authorities were concerned at the level of crime committed by juveniles forming artful gangs of pick pockets.

The regime at Little Mill was tough.

Petty theft and smoking were punished as was abusive language and “violence of temper”.

Boys worked on the farm which covered about 14 acres learned gardening skills and some gained RHS certificates.

The daunting prospect of turning wayward lads from a life of crime was soon to become a worthwhile achievement .

By 1912 the school had a medical officer, a dentist, a bandmaster and a drill master which, two years later on the outbreak of World War One, proved to be a distinct advantage when many boys from the newly formed Army Cadet Force enlisted and later served with the British Expeditionary Force in France.

Not all schools were as well conducted as Little Mill. Some proved to be inadequate in controlling the boys and in one notorious case in 1878 60 boys escaped after attacking the master with knives from the dining room.

Medical fitness was a key factor in the boys’ development and medical reports indicate there were

treatments for influenza, gastric problems and boils.

One report stated: "A case of congenital syphilis appears to be progressing satisfactorily”.

One boy was sent to a convalescent home in Llandrindod Wells for a month at a cost of two shillings and sixpence a week.

In the school’s early days in December 1865 a boy named William Crockett became ill with a medical condition which is not revealed. He later died. At a special meeting of the governors in January 1866 it was resolved “that we greatly lament that medical assistance was not called in earlier but are nevertheless of the opinion that it would not have caused a more favourable result.

“The Superintendent, Mr Samuel Arnold, was justified in administering the medicine and had no reason to anticipate the fatal result. The symptoms had been seen three weeks before and been removed by ordinary remedies.”

Many staff and boys attended the funeral and William was buried in Mamhilad Churchyard.

An early example of placing boys in work experience jobs came in 1912 but this attempt to improve their skills misfired through an oversight which earned a reprimand for not observing the school’s procedures.

It was common practice to send boys to work in local industries and one was sent to the GWR engine sheds in Newport without disclosing that he was from a reform school.

The school secretary was ordered to call on the station master to apologise for the oversight and to “use all necessary steps to ensure that his job would not be forfeited”.

Despite its success in reforming boys and with a low re-conviction rate the school fell victim to a re-organisation and on August 23, 1922, Little Mill closed its doors and 47 boys were transferred to other locations.

Before long all reformatories were classified as Approved Schools.

Redundancy pay for management gave staff one month’s salary for every year of service. To ensure some measure of fairness the Home Office stipulated that £10 should be taken from the bandmaster and clerk’s sum and given to the assistant matron and sewing mistress.

The school site has been redeveloped for houses that now mark the site which for 63 years became a notable and influential chapter in Monmouthshire’s judicial history.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here